Indian Reserves

In various ways in different parts of [British Columbia], Native life came to be lived in, around, and well beyond these reserves, but wherever one went, if one were a Native person, the reserves bore on what one could and could not do. They were fixed geographical points of reference, surrounded by clusters of permissions and inhibitions that affected most Native opportunities and movements. Once put in place, they had a long life. Only now, more than a hundred years after most of them were laid out, are they perhaps breaking down somewhat.

Cole Harris

Making Native Space, xxi.

What are Indian Reserves?

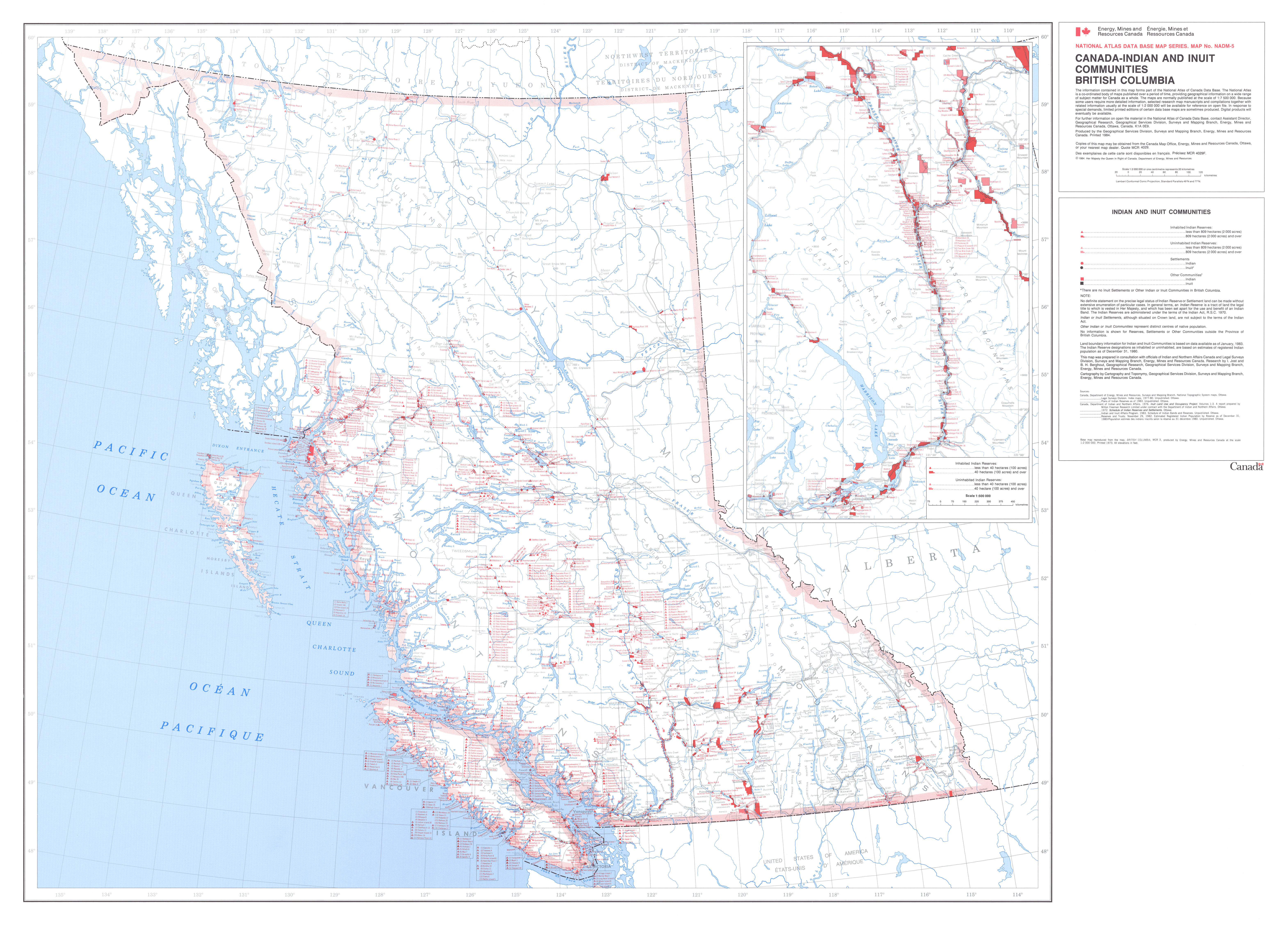

Map of Indian reserves in British Columbia, courtesy of Natural Resources Canada. Click to view the map in full.

An Indian Reserve is a tract of land set aside under the Indian Act and treaty agreements for the exclusive use of an Indian band. Band members possess the right to live on reserve lands, and band administrative and political structures are frequently located there. Reserve lands are not strictly “owned” by bands but are held in trust for bands by the Crown. The Indian Act grants the Minister of Indian Affairs authority over much of the activity on reserves. This overarching control is evident in the Indian Act’s definition of Indian reserves:

Reserves are held by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of the respective bands for which they were set apart, and subject to this Act and to the terms of any treaty or surrender, the Governor in Council may determine whether any purpose for which lands in a reserve are used or are to be used is for the use and benefit of the band.

The Indian Act further sets out the degree of control and authority that the Minister of Indian Affairs has over the use of reserve lands. For example, the Indian Act states that “No Indian is lawfully in possession of land in a reserve,” and that the Minister must approve any certificates of possession or similar forms of property ownership for on-reserve band members. The Indian Act further states that “the Minister may, in his discretion, withhold his approval and may authorize the Indian to occupy the land temporarily and may prescribe the conditions as to use and settlement that are to be fulfilled by the Indian before the Minister approves of the allotment.” You can read the Indian Act and its regulations over reserves online here: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/.

Creation of the reserve system

Precursors to the modern reserve system existed in Canada prior to Confederation and the Indian Act as products of the colonial drive to “civilize” Aboriginal peoples by introducing them to agriculture, Christianity and a sedentary way of life based on private property. As early as 1637, French missionaries had been entrusted by their church with lands to be set aside for their Indian charges. At Sillery in New France (now part of the Canadian province of Quebec), these settlements were created with the intention to encourage Aboriginal peoples to adopt Christianity.1 These first experiments would become a rough model for subsequent reserves in Canada.

Non-Aboriginal settlement of what is now Canada expanded as the British gained control of French colonies and the Dominion of Canada was formed in 1867. Newcomers began occupying the traditional territories of Aboriginal peoples in increasing numbers (some with the financial assistance of their governments). Colonial authorities and some Aboriginal people viewed the creation of reserves as a pragmatic solution to land disputes and conflicts between Aboriginal peoples and settlers. Reserve creation was not initially overseen by a central authority or administered by a central policy, and so practices varied between regions. In some cases, the Canadian government allotted Crown land for the purposes of forming of a reserve, whereas in other cases the Crown purchased private land to convert into reserves. At other times, the government entrusted missionaries with establishing reserves on designated Crown lands for the peoples they were working with.2

In Ontario, treaties reached with Aboriginal peoples in the 19th century, such as the Robinson treaties, included provisions for the creation of reserves. Under these treaties, Aboriginal groups agreed to share lands and resources with settlers in exchange for, among other things, the guarantee that traditional activities such as hunting and fishing would continue undisturbed. The Aboriginal signatories of these treaties understood that the lands would be shared and their practices respected, not that they would be confined within a small allotment indefinitely. (For more on this, see the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples, “Differing Assumptions and Understandings” in Looking Forward Looking Back, 1996.)

Colonial agents frequently insisted that a prime motive for establishing the reserve system was to encourage Aboriginal peoples to adopt agriculture. Yet many Aboriginal peoples found themselves displaced to lands generally unsuitable for agriculture, such as rocky areas with poor soil quality or steep slopes. Meanwhile, settlers were quickly securing the most fertile lands for themselves. (Ironically, years later, government agents would use First Nations’ minimal agricultural production—further hindered by discriminatory legislation that outlawed selling produce or livestock produced on the reserve—to justify reducing reserve lands even further.) By the time government authorities began to create reserves in British Columbia in the 1850s, it became apparent that the underlying motive for setting aside small tracts of land for Aboriginal peoples was to make available to newcomers the vast expanses of land outside reserve borders.

Reserves and traditional territory

A reserve is not to be confused with a First Nation’s traditional territory. Although reserve borders were imposed on First Nations, many First Nations have continued hunting, gathering, and fishing in off-reserve locations that they have used for many generations. In addition, important ceremonial sites may be located outside a reserve but continue to be significant for a band’s cultural and spiritual practices. When a First Nation describes its traditional territory, it is describing this larger land base that it has occupied and utilized for many generations, before reserve borders were imposed and drawn on maps. When a First Nation expresses concern about impacts to its traditional territory, its members are likely referring to the far reaching consequences for the nation’s socio-economic, spiritual, and cultural health. When issues of Aboriginal title are discussed, this generally refers to the use and enjoyment of traditional territories.

The reserve system undermined Aboriginal peoples’ relationship to their traditional territories but did not destroy it. As noted above, for many First Nations, off-reserve locations continue to serve as sites of economic, cultural and spiritual practices. The relationship to traditional territory also remains significant for many First Nations who have lost access to it, even if they are unable to continue such practices in those locations.

Reserve acreage varied across the country. Treaties 1 and 2 allotted 160 acres per family of five, whereas Treaties 3 to 11 granted 640 acres per family of five. In British Columbia, reserves were considerably smaller, with an average of 20 acres granted per family. Methods for determining the location of a reserve also differed. Some treaties called for reserves near important waterways that were crucial to the survival of the band in question, and some bands were consulted about reserve location. Some reserves were created entirely outside a First Nation’s traditional territory. Ultimately, many reserves are small and provide the respective bands with minimal resources or economic opportunities. Historian Keith Thor Carlson calls reserve creation in British Columbia, “the government’s attempt to skirt its political and legal obligation to negotiate with Aboriginal people and to provide compensation for alienated land and resources. In effect, it was an effort to extinguish Aboriginal title through administrative and bureaucratic means.”3

Reserve reduction in British Columbia

Reserves in British Columbia had barely been established before government officials moved to reduce them in size. In the late 1860s, the governor of British Columbia, Joseph Trutch, “cut off” what he deemed excess land from many of the province’s reserves under the pretense that Aboriginal people did not need so much land and that white settlers would make better use of it—an ethnocentric view that defined “productive use” as resource extraction and agriculture. These and other lands lost through successive reductions are known as “cut-off lands.” Many bands subsequently argued that their reserves were too small and location was poor. As geographer Cole Harris notes,

From the late 1860s, Native leaders [in British Columbia] had protested their small reserves in every way they could, claiming, fundamentally, that their people would not have enough food and that their progeny had no prospects. In retrospect, they were right. The spaces assigned to Native people did not support them, although the mixed economies they cobbled together, the revised diets they ate, and the accommodations and settlements they lived in had allowed some of them to survive.4

In response to these ongoing protests, in 1912 the federal and British Columbian governments together created the McKenna-McBride Commission to review reserve allotments across the province. However, the Commission ended up further reducing the size of many reserves, based on their criteria of proper usage (such as farming), criteria that differed greatly from that of the band. As Harris puts it, “the same government that took away most of their lands secured them in the possession of reserves, and then took away most of the reserves.”5

In addition, throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Canadian government passed legislation that enabled the government to expropriate parcels of reserve land without the consent of the band and without providing compensation, for the purpose of public utilities rights-of-way such as railways, transmission lines and highways. This has resulted in the fragmentation and disruption of many reserves. In many cases, the province or Crown further retains subsoil rights on the reserve, which means band members do not “own” the minerals found there. Coastal waters and tidal lands do not form part of the reserve either in most cases. Although colonists tried to justify the small sizes of many reserves along coastal British Columbia by their access to waterways, Aboriginal fishing grounds and their resources have been restricted by provincial and federal regulations. (For more information about this, see our section on Aboriginal Fisheries, as well as Douglas C. Harris, Landing Native Fisheries: Indian Reserves and Fishing Rights in British Columbia, 1849-1925, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.)

Impacts of the reserve system

The creation of reserves had far-reaching implications for all aspects of Aboriginal life. The reserve system was, on a fundamental level, a government-sanctioned displacement of First Nations. At the stroke of a pen, reserves divided up not only lands but peoples and Nations that had existed for hundreds if not thousands of years. Families, houses and clans that had hunted and gathered together for generations were abruptly and arbitrarily joined up with other families and houses, disrupting social networks and long-established kinship systems that determined who could hunt, fish, and gather in particular areas.

As a part of the Crown’s responsibilities for its new Indian wards, government officials sponsored the construction of housing on reserve. These houses were designed with the Western nuclear family unit in mind, and could not accommodate larger, more extensive Aboriginal families. Often shoddily built on a small government budget, housing became yet another foreign and divisive experience imposed by reserves.

The Odanak reserve in Quebec, in the territory of the Abanaki people. Photo by Axel Drainville. (c) Axel Drainville 2010. Photo source: Flickr

Initially, Aboriginal people were able to adapt to this government-imposed restructuring of their homelands and lifestyles. In 19th century British Columbia, for example, many Aboriginal women and men were employed in seasonal labour such as hop picking and cannery work. This allowed them to continue their seasonal ways of life, and to continue their hunting, gathering, and seasonal celebrations. At the start of the 20th century, however, First Nations peoples in British Columbia began to be marginalized from the capitalist workforce. This was partially due to growing competition from new immigrants (some of them willing to perform cheap labour) and to open racism in the hiring process.6 In addition, by the 1950s, advances in technology led to the mechanization of labour and further centralization of industry in urban centres far from reserve sites. Jobs such as hop picking simply disappeared.

Disruption of traditional networks, marginalization from the capitalist economy, as well as discriminatory legislation that outlawed resource distribution and severely limited Aboriginal people’s ability to fish and hunt, led to a rapid increase in poverty on reserves. Many Aboriginal people living on reserves suddenly found that they were unable to sustain themselves or their families. However, leaving the reserve meant facing discrimination and assimilation in urban centres, relinquishing one’s Indian rights, and losing or jeopardizing connections to family and territory.

This situation intensified into the mid-20th century as Aboriginal peoples, legally wards of the state, found few alternatives to accepting the minimal support offered by the federal government. This, along with discriminatory legislation and assimilationist programs such as the residential schools and the “Sixties Scoop,” has contributed to the situation that many reserves find themselves in today.

Nonetheless, as Cole Harris has observed, despite the radical changes brought by the reserve system,

Native lives were still being lived. There were still joys as well as sorrows in Native households. There were still Native people taking charge of their own lives and getting along in the different world that had overtaken them…Their identities were still Native, still Nisga’a, Tsimshian, Nuxalk, or Nlha7kapmx, and they still lived, for the most part, within the territories of their ancestors, yet detached in the particular geographies of settlement and circulation that the reserve system had brought into being.7

Challenges facing reserve communities today

Reserves today continue to be important land bases for First Nations across Canada, often contained within their ancestral and spiritual homelands. Yet, on average, reserves present some of the most alarming conditions in Canada. They are typically isolated communities with high instances of poverty, substance abuse, suicide, unemployment, and mortality. Some reserves exhibit what has been controversially described as Third World conditions, due to inadequate housing and contaminated water supplies, among other things. As Globe and Mail reporter Christie Blatchford wrote regarding the Yellow Quill First Nation in 2008, “The reserve water supply was so poor that until 2004, when a new water treatment system began operating, residents lived under a boil-water alert that lasted fully eight years. Would any community in Canada—but for one on a reserve—have had to endure such an alert for eight years?”8

The reasons for these socio-economic conditions on so many reserves across Canada are complex and the subject of ongoing dialogue and debate. However, it is widely accepted that the cultural genocide and social disruption perpetrated over generations through displacement, discriminatory legislation such as the Indian Act, and federal programs such as the residential school system created enduring hardships among Aboriginal peoples and hindered the re-establishment of social networks and the development of stable communities.

In addition to these social hardships, reserve communities often face economic and environmental challenges. Reserves are typically located in areas where economic opportunities are limited, and the reserves themselves provide few resources. Access to resources such as fish and timber are heavily regulated, and in many cases the government maintains ownership of any mineral or subsurface resources. (In British Columbia, this is addressed in the BC Indian Reserves Mineral Resources Act.) Because reserves are held in trust by the Crown, people living on them do not “own” the land. Property is not considered an asset, and band members generally face difficulty in obtaining mortgages, small business loans, or lines of credit. They also face more restrictions than private owners when it comes to developing their land. As well, government rights-of-way such as power transmission lines, railways and highways frequently intersect reserve lands, dividing them up and further reducing useable space.

The impacts of the reserve system also take on a gendered dimension. Aboriginal women on reserves face additional challenges with property, for example. Historically a woman has had to leave the reserve community she married into if her husband abandons her or passes away. In these cases, lack of regulation regarding on-reserve matrimonial property has forced many women to leave their homes and belongings behind as they leave the reserve. (See, for example, the Indigenous Services Canada’s resources on Matrimonial Real Property on Reserves, available at https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032553/1581773144281).

Reserves fall under federal rather than provincial or municipal jurisdiction—levels of government that typically provide services, infrastructure and regulations to non-reserve communities. In the spring of 2009, Sheila Fraser, the auditor general of Canada, concluded an audit of the environmental conditions of reserves. She found that there was a significant gap between environmental conditions in reserve communities and those in other communities in Canada. Non-reserve communities are regulated by provincial and municipal governments, which have systems in place to deal with waste disposal and air and water monitoring. Reserve communities, on the other hand, fall under the jurisdiction of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), as stipulated in the Indian Act. Fraser concluded that INAC lacks the capacity and resources and is generally unprepared to provide these services and regulations to reserve lands. In fact, the audit found that INAC has no idea how waste is disposed of in 80 reserve communities, a startling statistic that provides a glimpse into the breadth of challenges to overcome.9

A cultural, spiritual, and physical homeland

Understanding the reserve system can be complicated. While reserves were initially created to further the colonial agenda of assimilation, in time this objective competed with others, such as facilitating European settlement. As a result, reserves were typically created in isolated areas away from non-Aboriginal settlements, perpetuating a stark segregation between Native and non-Native populations. Ironically, this situation has contributed to maintaining Aboriginal community ties and cultural reproduction. The widely held colonial belief that, in time, Aboriginal peoples would either die out or enfranchise and assimilate into mainstream Euro-Canadian society was not borne out, due in part to the nature of the reserve system itself.10

A reserve can provide a community in which Aboriginal people feel free to practice their cultures and customs, live close to their extended families, and raise their children in their cultural and ancestral homelands. This reserve environment can allow band members to promote cultural values and teachings and sustain the culture’s vitality. Reserves are, therefore, a disruptive and in many ways destructive imposition that, through the strength of the peoples who occupy them, often simultaneously support cultural survival.

The reserve system is a paradox that closely resembles that of the Indian Act. As with the Indian Act, some Canadians believe the government should do away with the reserve system entirely, arguing that reserve lands are anachronistic and serve solely to perpetuate the segregation of Aboriginal peoples in isolated parcels of land. Some people argue that the reserve system is a form of apartheid and should therefore be abolished. However, these arguments fail to take into account that, along with having a distinct legal and political status, reserves provide a physical space for building and preserving community, usually within Aboriginal peoples’ traditional territories. Proposals to abolish such policies have frequently been met with widespread resistance from First Nations across Canada. In 1969, the Canadian government issued a White Paper that proposed, among other things, that “control of Indian lands be transferred to the Indian people.”11 The Indian Association of Alberta’s response to this proposal echoed the feelings of many First Nations leaders and community members at the time:

We agree with this intent but we find that the Government is ignorant of two basic points. The Government wrongly thinks that the Indian Reserve lands are owned by the Crown. These lands are “held” by the Crown but they are Indian lands. The second error the Government commits is making the assumption that Indians can have control of their land only if they take ownership in the way that ordinary property is owned. Control of Indian lands should be maintained by the Indian people, respecting their historical and legal rights as Indians.12

While the above exchange took place in 1969, these debates continue today. Some continue to argue that reserves should be converted into fee simple, or privately-owned, lands. Those who do not agree with this approach point out that this proposal, frequently made by non-Aboriginal Canadians, is based on Western conceptions of private property, and operate on the assumption that the only “solution” to the challenges reserve communities in Canada face is to assimilate into non-Aboriginal “white” society and adopt non-Aboriginal lifestyles. Many leaders and activists maintain that they can work towards overcoming the challenges of the reserve system and simultaneously retain their Aboriginal ways of life. Further, to simply abolish the reserve system absolves the Canadian government of its legally-binding obligations and commitments it made to First Nations.

As with the Indian Act and related policies, the reserve system is highly problematic. However, reserves also represent First Nations’ unique relationship with the Canadian state and highlight the state’s obligations to Aboriginal peoples—and, perhaps, its lack of commitment to them.

By Erin Hanson

Recommended Resources

Reserves nationwide

Bartlett, Richard H. Indian Reserves and Aboriginal Lands in Canada: A Homeland. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan, Native Law Centre, 1990.

Frideres, James S., and René R. Gadacz. “Profile of Aboriginal People I: Population and Health.” Chap. 3 in Aboriginal Peoples in Canada, 56–92. 8th ed. Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008.

Reserves in British Columbia

Harris, Cole. Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002.

Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. Our Homes Are Bleeding—Digital Collection. Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs. http://ourhomesarebleeding.ubcic.bc.ca

A fantastic resource about reserves and the cut-off lands in B.C., including the testimonies of those affected first-hand by the McKenna-McBride Commission, maps, photographs, and other archival documents.

Ware, Reuben. Our Homes are Bleeding: A Short History of Indian Reserves. Victoria: Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, Land Claims Centre, 1975. Available online: https://arcabc.ca/islandora/object/tru%3A1645

Endnotes

1 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, “The Imposition of a Colonial Relationship,” in Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, vol. 1, Looking Forward, Looking Back (Ottawa: The Commission, 1996).

2 Ibid.

3 Keith Thor Carlson, “Indian Reservations,” in A Stó:lō Coast Salish Historical Atlas, (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre), 2001, 94.

4 Cole Harris, Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002), 291.

5 Harris, 58.

6 Keith Thor Carlson, You Are Asked to Witness: The Stó:lo in Canada’s Pacific Coast History, (Chilliwack: Stó:lō Heritage Trust, 1997), 120–1.

7 Harris, 291-2.

8 Christie Blatchford, “Blatchford’s Take: Shame and Disgrace—Canada’s native reserves deserve foreign correspondent treatment,” The Globe and Mail, February 2, 2008. Available online via https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/canadas-native-reserves-deserve-foreign-correspondent-treatment/article717978/. Accessed May 2010.

9 Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Land Management and Protection on Reserves,” 2009 Fall Report of the Auditor, sec. 6.59. Available online via http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_200911_06_e_33207.html. Accessed May 2010.

10 Harris, xvi.

11 Canada, Indian and Northern Affairs.Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy. Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1969. Available online via http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/301/inac-ainc/indian_policy-e/cp1969_e.pdf Accessed December 2020.

12 Indian Association of Alberta. Citizens Plus. (“The Red Paper.”) Edmonton: Indian Association of Alberta, 1970.