In 1974, Jean Chretien, Canada’s Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND) faced a dilemma. Oil and gas exploration in the Canadian north had boomed after the discovery of a large pool of oil at Prudhoe Bay in Alaska. The petroleum industry had served notice that if commercial quantities of oil and gas were discovered, the industry would apply to build a pipeline down the Mackenzie Valley and ship the hydrocarbons to markets in the United States.

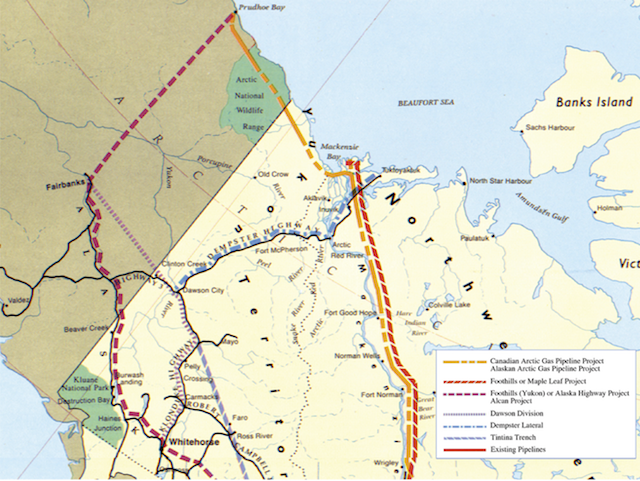

Two pipeline companies proposed different routes. Canadian Arctic Gas Pipelines (CAGPL), a consortium of 80 US and Canadian companies, wanted to build a pipeline that would take natural gas from Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope of Alaska, across the north coast of the Yukon to the Mackenzie Delta. Canadian natural gas would be added and the line would continue south to the United States.

The “Maple Leaf” route was proposed by Foothills Pipelines, a consortium of Alberta and BC-based companies. Foothills wanted to pipe natural gas from the Mackenzie Delta south to Canadian markets. This route relied on finding enough natural gas in the Delta to justify the pipeline’s construction.

Canada Today/Aujourd’hui, Volume 8, #5, Canadian Embassy, Washington, DC, 1977. (Click image for a larger version)

Within the same period, aboriginal organizations in the north had begun grass roots movements to claim the lands which the pipeline would cross. The Committee for Original People’s Entitlement (COPE), representing the Inuvialuit of the Mackenzie Delta, began a house-to-house campaign to explain the land claim to families in six communities around the Beaufort Sea.

In Yellowknife, the chiefs at the Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories had attempted to file a legal caveat claiming an interest in 450,000 square miles (1,000,000 sq. km.) of the Northwest Territories. If the caveat were successful, the lands planned for the pipeline right-of-way would belong to the Dene.

The federal government argued that the signing of Treaties 8 and 11 had extinguished the Dene’s interest in their traditional lands. Justice Morrow of the Supreme Court of the NWT was asked to rule on whether the caveat could be filed.

Justice Morrow took his court to small communities across the NWT to hear evidence from Dene elders who recalled the signing of the treaties. They said the treaties were peace agreements, not a surrender of the land. Justice Morrow ruled that the caveat could be filed.

Meet Thomas Berger

A decade ago, colleagues in the Peter A. Allard School of Law began to capture the stories of lawyers and First Nations leaders who were involved in the earliest Indigenous rights cases heard in Canadian courts.

Vancouver lawyer Thomas Berger, a graduate of UBC, was a key figure in two of these cases: the Snuneymuxw case on Vancouver Island (R v. White and Bob) and the Nisga’a case from northern BC (Calder v. BC). As Justice Thomas Berger, he went on to lead the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, a Royal Commission into a proposed pipeline across the land of the Inuvialuit and Dene peoples of the Northwest Territories.

This documentary tells the story of Tom Berger from his childhood in Victoria to the moment when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau selected him to lead the Inquiry. It provides a glimpse into the early days of the on-going battle to secure Indigenous rights in Canada.

Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry

To resolve the looming conflict between the petroleum companies and the aboriginal organizations, DIAND Minister Jean Chretien asked Justice Thomas Berger of the Supreme Court of British Columbia to lead the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry.

Thomas Berger (photo by Michael Jackson)

Berger organized an inquiry that was markedly different from those of the past.

- For the first time, environmental and aboriginal organizations received funding to present their own expert witnesses at the Formal hearings held in Yellowknife.

- Professor Michael Jackson of the University of BC organized hearings in more than 30 Dene, Inuit and non-aboriginal communities across the NWT so residents could offer testimony.

- The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation created an aboriginal news team that would broadcast nightly reports from the Inquiry in six languages.

- Special Counsel Ian Waddell organized hearings in cities across southern Canada so that all Canadians could express their views.

The Report

The Inquiry’s final report was released on May 9, 1977. It was an instant best seller, with 10,000 copies in circulation by the end of the first week.

The original terms of the Inquiry did not permit Judge Berger to recommend against a pipeline, but the report did propose ways to strike a balance between pipeline construction and the protection of the environment and aboriginal rights.

The Berger Inquiry Project gives you a way to explore this history in depth. Click on the image below here to enter the project site.

![]()