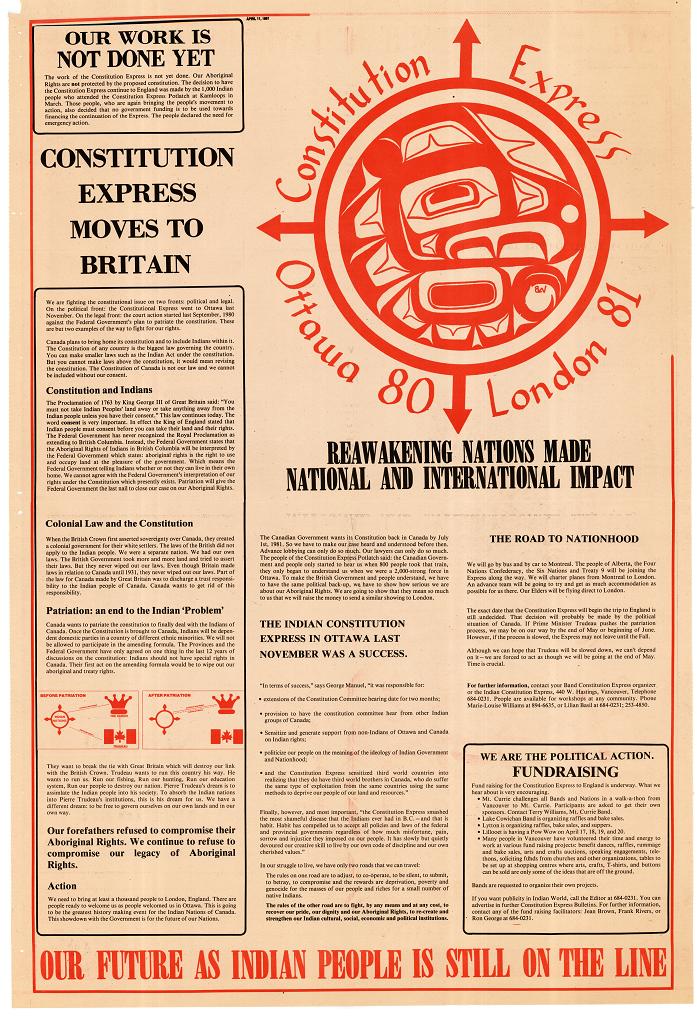

The Constitution Express was a movement organized in 1980 and 1981 to protest the lack of recognition of Aboriginal rights in the proposed patriation of the Canadian constitution by the Trudeau government. A group of activists led by George Manuel, then president of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs chartered two trains from Vancouver that eventually carried approximately one thousand people to Ottawa to publicize concerns that Aboriginal rights would be abolished in the proposed Canadian Constitution. When this large-scale peaceful demonstration did not initially alter the Trudeau government’s position, delegations continued on to the United Nations in New York, and then to Europe to spread their message to an international audience. Eventually, the Trudeau government agreed to recognize Aboriginal rights within the Constitution. Contemporary activist Arthur Manuel calls the Constitution Express the most effective direct action in Canadian history, as it ultimately changed the Constitution.1

What was the patriation, and why were First Nations opposed to it?

Before 1982, Canada was a dominion of Britain. At that time, instead of having its own constitution, Canada was governed by the British North America (BNA) Act. The Canadian Constitution fell under British law, which meant that only the British Parliament could change Canadian law. Patriating the Constitution would give Canada authority to amend its own laws and make it functionally a more independent country, and in October of 1980, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau introduced a resolution to patriate the Constitution. This resolution was developed with no consultation with any Aboriginal organizations, and the proposed constitution made little reference to Aboriginal rights. Many Aboriginal leaders were concerned that the patriation would essentially remove Canada’s responsibility to recognize Aboriginal rights and title.

The Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC), a political organization representing bands across British Columbia, viewed the position of First Nations within the Commonwealth as sovereign nations in their dealings with two other nations: Canada and Britain.2 UBCIC understood that the Constitution Act as it was proposed would delegate British authority to the provincial and federal governments of Canada, but with no recognition of Aboriginal governments.3 UBCIC maintained that “Britain and Canada’s duties with respect to Aboriginal Nations are a result of International law and not any domestic law of Canada.”4 Treaties between Britain and First Nations preceded the BNA Act, and therefore, in their position paper, the UBCIC argued that “these agreements and not the BNA Act are the foundation of which the international rights of Aboriginal Nations are based and the only hope for our future survival as a people.”5

UBCIC’s concerns about the patriation included:

- That agreements between the British crown and First Nations that had established First Nations rights, such as in treaties and proclamations, might no longer hold legal weight, as the Constitution excluded any reference to them.6

- That First Nations would not be recognized as parties in decision-making on a federal level.7

- That ambiguity surrounded sectionsthat were to prevent discrimination and protect “traditional rights and freedoms” for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.8

- That if the federal government merged their social programs for Aboriginal peoples with those provided on the provincial level for mainstream society, it would undermine the specific needs of Aboriginal peoples across Canada.9

- That there was no consultation with First Nations about the patriation.

- That the patriation appeared to be another assimilationist policy, much like the 1969 White Paper.10

The Constitution Express from Vancouver to Ottawa, New York, and London

In order to bring national and international attention to the issue, as well as to potentially delay the patriation of the Constitution, George Manuel, then president of the UBCIC, chartered the train to take Aboriginal leadership and community members from Vancouver to Ottawa. On November 24, 1980, two trainloads of people left Vancouver for Ottawa. The train made stops throughout Canada in order to spread their message to communities and the media. More supporters joined the train along the way and by the time they reached Ottawa, there were about one thousand people on board. Vicki George, daughter of organizer and participant Ron George, recalls the personal sacrifices that many participants made in order to take part in this movement, such as selling personal belongings to raise funds and spending considerable time away from their families— a testament to just how crucial this movement was for them.11

The train, however, was not always met with support. Arthur Manuel, for instance, recalls a bomb threat made against it while in Winnipeg.12 Dr Winona Wheeler, on board as a representative of the UBCIC, recalls that the bomb threat was in fact staged by undercover RCMP officers posing as train employees in order to delay the train and to intimidate the activists.13 The train was stopped in remote, rural Ontario, and the passengers’ belongings were searched. Despite the unsettling hold up, the train continued on to Ontario. Click here to listen to Winona describe the events that day.

As the Constitution Express travelled across Canada, it was given much media attention with footage almost daily on televised news broadcasts. This led to a remarkable welcome in Ottawa when Mayor Marion Dewar called on the citizens of Ottawa to generously open their home to the strangers arriving on the Constitution Express train:

…[T]he media was picking up on us. A couple days, about three days before the train arrived, Marion Dewar, the mayor of Ottawa came to us and asked us how we were doing and we told her, well, we only had about, we could count the number of billets we’d arranged on our hands, and the food wasn’t coming along too well. We were trying to raise awareness about food. So she says, ‘Well, I think you guys need some help,’ and she just went on air and had a big press release and called on the citizens of Ottawa to respond with their friendship and help, and lo and behold, they did.

Despite the warm welcome and support from Ottawa citizens and mayor, the Constitution Express’s arrival in Ottawa did not initially change Trudeau’s position. As a result, 41 people immediately continued on to the United Nations headquarters in New York City, and presented their concerns before the United Nations to gain international attention.15

In 1981, the Constitution Express continued across the Atlantic onto Europe, making this now an international demonstration. The Constitution Express travelled to the Netherlands, Germany, France, Belgium, and then England in order to present the concerns and experiences of Aboriginal peoples across Canada to an international audience. They were met with support, and convinced many politicians and members of the House of Lords (now known as the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom) to support Indigenous rights.16 Subsequently, after months of international attention and pressure from Aboriginal groups across Canada, the Canadian government agreed to specifically recognize Aboriginal rights within the new constitution.

The Outcome of the Constitution Express – Section 35 is added

By late January 1982, and after extended negotiations with Aboriginal leaders, the federal government agreed to the demands of Aboriginal organizations.17 Section 35 was added to the Canadian Constitution to specifically recognize and affirm Aboriginal and treaty rights. Eventually, Section 37 was also amended, obligating the federal and provincial governments to consult with Aboriginal peoples on any further outstanding issues.18 The obligation to consult lead to discussions over the following year to further develop Section 35—subsections (3) and (4) were added in 1983. For more information on the development of Section 35 and what it means, please read

By Erin Hanson.

Recommended resources

The Constitution Express: A Multimedia History (DVD). Produced by Vicki L. George for UBCIC & UBC, 2007.

Available at UBCIC Resource Centre, and can be viewed online via UBCIC’s Constitution Express Digital Collectionn at http://constitution.ubcic.bc.ca/node/133

Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, “Constitution Express Digital Collection.” http://constitution.ubcic.bc.ca/

A fantastic online resource that includes further information such as timelines, newspaper articles, UBCIC papers, archived petitions, and video interviews.

Endnotes

1 Manuel, Arthur. Guest lecture, Introduction to First Nations Studies. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. 24 March 2009.

2 UBCIC, Indian Constitution Express. 1981, 7.

3 Ibid., 1

4 Ibid., 2.

5 Ibid., 3.

6 Ibid., 5.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid, 6.

9 Ibid, 6-7.

10 UBCIC, “Editorial,” UBCIC News. June 1978, 2.

11 George, Vicki. Personal communication; Thursday, June 18, 2009.

12 Manuel.

13 Interview with Dr Winona Wheeler, The Constitution Express: A Multimedia History. Produced by Vicki L. George for UBCIC & UBC, 2007.

14 Interview with Ron George. The Constitution Express: A Multimedia History.

15 UBCIC, UBCIC Bulletin, Oct 1981.

16 Manuel.

17 Smith, Melvin. “Some Perspectives on the Origin and Meaning of Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.” Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2000. Available online: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/PerspectivesonSection35.pdf

18 Romanow, Roy J., Howard A. Leeson and John D. Whyte. Canada… Notwithstanding: The making of the Constitution 1976-1982. Toronto: Carswell/Methuen, 1984. 121-2.